Where Are Nitrates and Nitrites Found?

Upon completion of this section, you will be able to

- Identify sources of nitrates and nitrites.

Understanding the environmental fate of nitrates and nitrites may help pinpoint potential sources of exposure. This would be important in assessment of patient exposure risk, prevention and mitigation of nitrate/nitrite overexposure and in the prevention of adverse health effects from exposure.

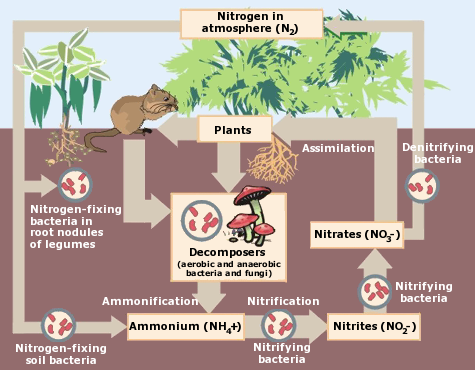

In general, the following describes the activity of nitrates and nitrites in the environment (as illustrated in Figure 2). Microbial action in soil or water decomposes wastes containing organic nitrogen into ammonia, which is then oxidized to nitrite and nitrate.

- Because nitrite is easily oxidized to nitrate, nitrate is the compound predominantly found in groundwater and surface waters.

- Contamination with nitrogen containing fertilizers (e.g. potassium nitrate and ammonium nitrate), or animal or human organic wastes, can raise the concentration of nitrate in water.

- Nitrate containing compounds in the soil are generally water soluble and readily migrate with groundwater [ATSDR 2006; EPA 2004; Mackerness and Keevil 1991; Shuval and Gruener 1992].

Shallow, rural domestic wells are those most likely to be contaminated with nitrates, especially in areas where nitrogen based fertilizers are in widespread use [Dubrovsky and Hamilton 2010; NRC 1995].

- Approximately 15 percent of Americans rely on their own private drinking water supplies which are not subject to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standards, although some state and local governments do set guidelines to protect users of these wells [Census Bureau 2011 and 2012].

- In agricultural areas, nitrogen-based fertilizers are a major source of contamination for shallow groundwater aquifers that provide drinking water [Dubrovsky and Hamilton 2010; CDC 1995].

- A recent United States Geological Survey study showed that 7 percent of 2,388 domestic wells and about 3 percent of 384 public-supply wells nationwide were contaminated with nitrate levels above the EPA drinking water standard of 10 parts per million (ppm) or 10 mg/L [Dubrovsky and Hamilton 2010].

- Elevated concentrations were most common in domestic wells that were shallow (less than 100 feet deep) and located in agricultural areas because of relatively large nitrogen sources, including septic systems, fertilizer use, and livestock [Dubrovsky and Hamilton 2010].

- Although suppliers of public water sources are required to monitor nitrate concentrations regularly, few private rural wells are routinely tested for nitrates [EPA 1990a; EPA 2007; CDC 2009].

- During spring melt or drought conditions, both domestic wells and public water systems using surface water can show increased nitrate levels [Nolan et al. 2002; Dubrovsky and Hamilton 2010].

- Drinking water contaminated by boiler fluid additives may also contain increased levels of nitrites [CDC 1997].

- Mixtures of nitrates/nitrites with other well contaminants such as pesticides and VOCs have been reported [Squillace et al 2002].

Nitrate and nitrite overexposure has been reported via ingestion of foods containing high levels of nitrates and nitrites. Inorganic nitrates and nitrites present in contaminated soil and water can be taken up by plants, especially green leafy vegetables and beetroot [Butler and Feelisch 2008].

- Contaminated foodstuffs, prepared baby foods, and sausage/meats preserved with nitrates and nitrites have caused overexposure in children [Savino et al. 2006; Greer and Shannon 2005; Sanchez-Echaniz et al. 2001; Dusdieker et al. 1994; Rowley 1973].

- Although vegetables are seldom a source of acute toxicity in adults, they account for about 80% of the nitrates in a typical human diet [Hord 2011; Pennington 1998].

- Celery, spinach lettuce, red beetroot and other vegetables (See Table 1) have naturally greater nitrate content than other plant foods do [Hord 2011; EFSA 2008; Keating et al. 1973; Vittozzi 1992].

- The remainder of the nitrate in a typical diet comes from drinking water (about 21%) and from meat and meat products (about 6%) in which sodium nitrate is used as a preservative and color-enhancing agent [Alexander et al. 2010; Gilchrist et al. 2010; Lundberg et al. 2009; Lundberg et al. 2008; Norat et al. 2005; Chan 1996; Saito et al. 2000].

- For infants who are bottle-fed, however, the major source of nitrate exposure is from contaminated drinking water used to dilute formula [Hord et al. 2010; EPA 2007].

- Bottled water is regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a food. It is monitored for nitrates, nitrites and total nitrates/nitrites.

Table 1. Nitrate Content of Selected Vegetables

| Vegetable | Nitrate content, mg/100g fresh weight |

|---|---|

| Celery, lettuce, red beetroot, spinach | Very High (> 2500) |

| Parsley, leek, endive, Chinese cabbage, fennel | High (100-250) |

| Cabbage, dill, turnip | Medium (50-100) |

| Broccoli, carrot, cauliflower, cucumber, pumpkin | Low (20-50) |

| Artichoke, asparagus, eggplant, garlic, onion, green bean, mushroom, pea, pepper, potato, summer squash, sweet potato, tomato, watermelon | Very Low (<20) |

[Adapted from Hord et al. 2011; Santamaria 2006]

Nitrate or nitrite exposure can occur from certain medications and volatile nitrite inhalants.

Accidental and inadvertent exposures to nitrites as well as ingestion in suicide attempts have been reported [Aquanno et al. 1981; Gowans 1990; Ellis et al. 1992; Bradberry et al. 1994; Saito et al. 1996 and 2000; EPA 2007; Harvey et al. 2010].

Deliberate abuse of volatile nitrites (amyl, butyl, and isobutyl nitrites) frequently occurs [Wu et al. 2005; Lacy and Ditzler 2007]. Amyl nitrite (nicknamed by some as “poppers”) is used commercially as a vasodilator and butyl/isobutyl nitrites can be found in products such as room air fresheners [Kurtzman et al. 2001; Hunter et al. 2011].

Fatalities have been reported in adults exposed to nitrates in burn therapy [Kath et al 2011]; however infants and children are especially susceptible to adverse health effects from exposure to topical silver nitrate used in burn therapy [Cushing et al. 1969; Chou et al. 1999; Nelson and Hostetler 2003].

Other medications implicated in methemoglobinemia include

- Quinone derivatives (antimalarials),

- Nitroglycerine,

- Bismuth subnitrite (antidiarrheal),

- Ammonium nitrate (diuretic),

- Amyl and sodium nitrites (antidotes for cyanide and hydrogen sulfide poisoning),

- Isosorbide dinitrate/tetranitrates (vasodilators used in coronary artery disease therapy),

- Benzocaine (local anesthetic), and

- Dapsone (antibiotic).

Other possible sources of exposure include, ammonium nitrate found in cold packs and nitrous gases used in arc welding are other possible sources of exposure.

An ethyl nitrite folk remedy called “sweet spirits of nitre” has caused fatalities [Coleman and Coleman 1996; Dusdieker and Dungy 1996].

- Shallow, rural domestic wells are those most likely to be contaminated with nitrates, especially in areas where nitrogen based fertilizers are in widespread use.

- Other nitrate sources in well water include seepage from septic sewer systems and animal wastes.

- Foodstuffs high in nitrates, home prepared baby foods, and sausage/meats preserved with nitrates and nitrites have caused overexposure in children.

- Nitrate or nitrite exposure can occur from certain medications and volatile nitrite inhalants.