What Is the Biologic Fate of Nitrates and Nitrites in the Body?

Exposure to nitrates and nitrites may come from both internal nitrate production and external sources.

Intake of some amount of nitrates is a normal part of the nitrogen cycle in humans.

The mean intake of nitrate per person in the United States is about 40-100 milligrams per day (mg/day) (in Europe it is about 50-140 mg/day).

Nitrate can be synthesized endogenously from nitric oxide (especially in the case of inflammation), which reacts to form nitrite [Hord 2011; ATSDR 2004; Mensinga et al. 2003].

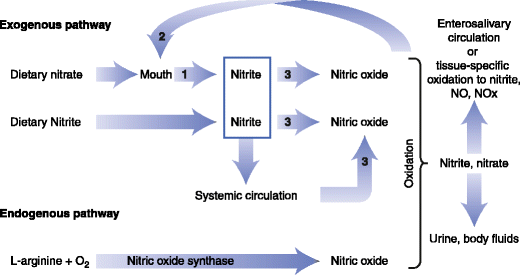

Figure 3 shows ways that nitrate, nitrite and nitric oxide can be produced and utilized from exogenous and endogenous sources [Hord et al 2009; Hord 2011].

In the proximal small intestine, nitrate is rapidly and almost completely absorbed (bioavailability at least 92%) [Mensinga et al. 2003; Carlsson et al. 2001].

- Inorganic nitrate/nitrite can be absorbed via inhalation [Holmes et al 2005; Gladwin et al. 2004].

- Inorganic nitrate/nitrite does not undergo first pass metabolism [Pannala et al. 2003; Omar et al. 2012].

Inorganic nitrates/nitrites are distributed widely through the circulation with approximately 25% of absorbed nitrate concentrating in the salivary glands [Carlsson et al. 2001].

Salivary, plasma, and urinary levels of nitrate and then nitrite rise abruptly after ingestion [Doel et al. 2005; Duncan et al. 1995; Walker 1996].

An increase in inorganic nitrite levels peaks around 3 hours post ingestion and can be detected about an hour after ingestion [Hunault et al. 2009; Gago et al. 2008].

The two main metabolic pathways for inorganic nitrates/nitrites are

- The nitrate-nitrite-NO pathway (Figure 3) and

- Enterosalivary circulation pathway (nitrate reductase activity of bacteria on the tongue generates nitrite and nitrite which is metabolized to NO in the stomach and circulation) [Hord 2011].

Approximately 5%-10% of the total nitrate intake is converted to nitrite by bacteria in the saliva, stomach, and small intestine [Hord 2011].

- In vivo conversion of nitrates to nitrites significantly enhances nitrates’ toxic potency.

- This reaction is pH dependent, with no nitrate reduction occurring below pH 4 or above pH 9.

- The high pH of the infant gastrointestinal system makes them more susceptible to nitrite toxicity from elevated nitrate/nitrite ingestion.

The metabolic pathway of plasma and tissue nitrates depends on local conditions such as tissue oxygenation, and inflammatory state. In the skin, local conditions also include ultraviolet light exposure [Mowbray et al 2009; Oplander et al. 2009].

Nitrate can be reduced to nitrite and nitric oxide when needed physiologically or as part of pathological processes (see Figure 3 [Hord 2011; van Fassen et al. 2009; Weitzberg et al. 2010; Kapil et al. 2010; Panesar 2008; Rocha et al. 2011; Webb et al. 2008; Jiang et al. 2008].

Mammalian metalloproteins and enzymes that have nitrate reductase activity include aldehyde oxidase, heme proteins, mitochondria and xanthine reductase [Hord 2011; Larsen et al. 2011; Jansson et al. 2008].

The reaction of nitrite with endogenous molecules to form N-nitroso compounds may have toxic or carcinogenic effects [ATSDR 2004; Powlson et al. 2008; Rao et al. 1982].

- Approximately 60% to 70% of an ingested nitrate dose is excreted in urine within the first 24 hours [Carlsson et al. 2001].

- About 25% is excreted in saliva through an active blood nitrate transport system and potentially is reabsorbed [Doel et al. 2005; Hord 2011].

- Half-lives of parent nitrate compounds are usually less than 1 hour; half-lives of metabolites range from 1 hour to 8 hours [Walker 1996; EPA 1990b].

- In the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals, urinary levels of nitrate were measured in a subsample of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)consisting of participants aged 6 years and older during 2007-2008. The geometric mean for urinary nitrate (in mg/g of creatinine) for the US population aged 6 years and older during 2007-2008 was 47.7, with a 95% confidence interval of 45.9-49.7 [CDC 2013]. Note that these measurements are used in population based public health research and not intended for clinical decision making on individual patients.

Fig. 3 A schematic diagram of the physiologic disposition of nitrate, nitrite, and nitric oxide (NO) from exogenous (dietary) and endogenous sources. The action of bacterial nitrate reductases on the tongue and mammalian enzymes that have nitrate reductase activity in tissues are noted by the number 1. Bacterial nitrate reductases are noted by the number 2. Mammalian enzymes with nitrite reductase activity are noted by the number 3 [Adapted from Hord et al. 2009].

- Exposure to nitrate and nitrites may come from both internal nitrate production and external sources.

- Intake of some amount of nitrates is a normal part of the nitrogen cycle in humans.

- Nitrate can be reduced to nitrite and nitric oxide when needed physiologically or as part of pathological processes depending on local conditions such as inflammation and tissue oxygenation.

- In vivo conversion of nitrates to nitrites significantly enhances nitrates’ toxic potency.

- Approximately 5%-10% of the total nitrate intake is converted to nitrite by bacteria in the saliva, stomach, and small intestine.

- 60-70% of an ingested nitrate dose is excreted in urine within 24 hours.