At a glance

This page summarizes the findings of analysis of data from all exposure assessment (EA) sites. Individual reports were published detailing the findings from each site.

Where EAs were conducted

The EAs were conducted in:

- Westhampton Beach and Quogue Area, New York (NY pilot EA)*

- Montgomery and Bucks Counties, Pennsylvania (PA pilot EA)*

- Hampden County, Massachusetts (Westfield EA)

- Berkeley County, West Virginia (Berkeley County EA)

- New Castle County, Delaware (New Castle County EA)

- Spokane County, Washington (Airway Heights EA)

- Lubbock County, Texas (Lubbock County EA)

- Fairbanks North Star Borough, Alaska (Moose Creek EA)

- El Paso County, Colorado (Security-Widefield EA)

- Orange County, New York (Orange County EA)

*We refer to the two pilot PFAS exposure assessments as "pilot EAs" and the remaining eight EAs as "ATSDR-led EAs." Although similar data were collected for all sites, the methods were slightly different. Only the blood data from the pilot EAs were combined with ATSDR-led EAs in the analyses on this page.

Why these sites were selected

When selecting EA sites, ATSDR considered the:

- Extent of PFOA and PFOS contamination in drinking water supplies.

- Duration over which exposure may have occurred.

- Number of potentially affected residents.

These ten sites were identified with PFAS drinking water contamination from use of products such as aqueous film forming foam (AFFF). The two pilot EAs were implemented by state agencies under cooperative agreements with ATSDR. The remaining eight were led by ATSDR.

Possibly as early as the 1970s, Air Force and Air National Guard bases used AFFF containing PFAS for firefighter training. AFFF was also used to respond to fires. Over time, these PFAS entered the ground, moved to offsite locations, and affected drinking water supplies like municipal wells, private wells, or surface drinking water.

Exposures were mitigated (reduced) at all sites through corrective actions by either:

- Removing contaminated water sources.

- Installing filtration and treatment systems.

- Or providing alternative drinking water supplies.

Each community reached final mitigation between 2014 and 2019.

Based on information available to ATSDR, all households in affected areas across the EAs now have a drinking water supply with PFAS concentrations that meet or are below current federal and state guidelines for PFAS in drinking water.

ATSDR does not recommend that community members who get drinking water from any of the affected public water systems use alternative sources of water.

For affected private wells, ATSDR recommends community members continue to use the alternative sources of water or filtration systems provided to them.

How participants were selected

Each ATSDR-led EA site focused on a specific area with known or expected PFAS exposure.

Households were randomly selected to participate within some site areas. At other sites, all households were invited to participate to ensure meaningful results. The selection process allowed ATSDR to estimate exposure to PFAS for the entire community within the geographic area, even those who were not tested.

Across the 10 EA sites, we analyzed the blood samples of 2,384 residents from 1,212 households. Not all participants completed the data collection activities.

Key takeaways

Overall, average age-adjusted perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS) blood levels are higher than national levels in all EA communities. PFOS and PFOA blood levels are higher than national levels in most EA communities.

In addition, elevated blood levels may result from past drinking water contamination in those communities. Some demographic and lifestyle traits are linked with higher PFAS blood levels.

All tap water samples collected during the ATSDR-led EAs were below EPA's 2016 health advisory and state public health guidelines for PFAS in drinking water. Two tap water samples had concentrations of PFOS above ATSDR's environmental media evaluation guide (EMEG) for PFOS in drinking water.

EMEGs represent estimated contaminant concentrations below which humans exposed during a specific timeframe (acute, intermediate, or chronic) are not expected to experience noncarcinogenic health effects. Drinking water EMEGs are derived from the corresponding oral MRLs using conservative assumptions of intake rate and body weight.

What was learned about PFAS in blood

Since 1999, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) has measured PFAS levels in blood in the U.S. PFAS levels are shown to be age dependent. They also tend to increase with age due in part to longer periods of exposure.

ATSDR adjusted blood levels of EA participants to the age distribution of the U.S. population during NHANES 2015-2016. Age adjustment enabled more meaningful comparison to the national average.

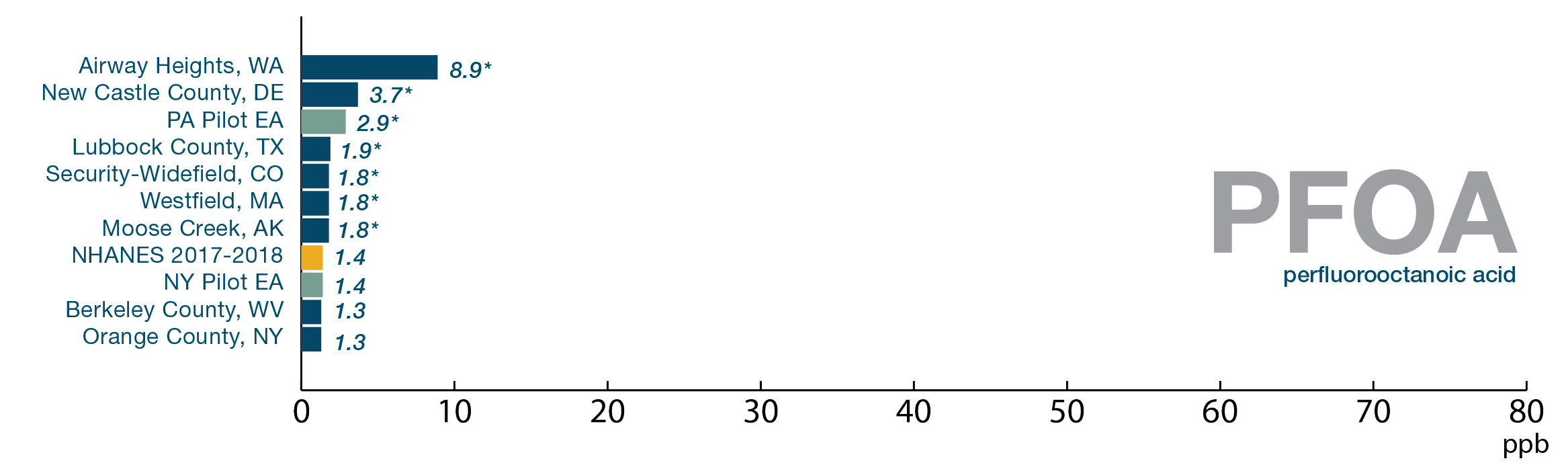

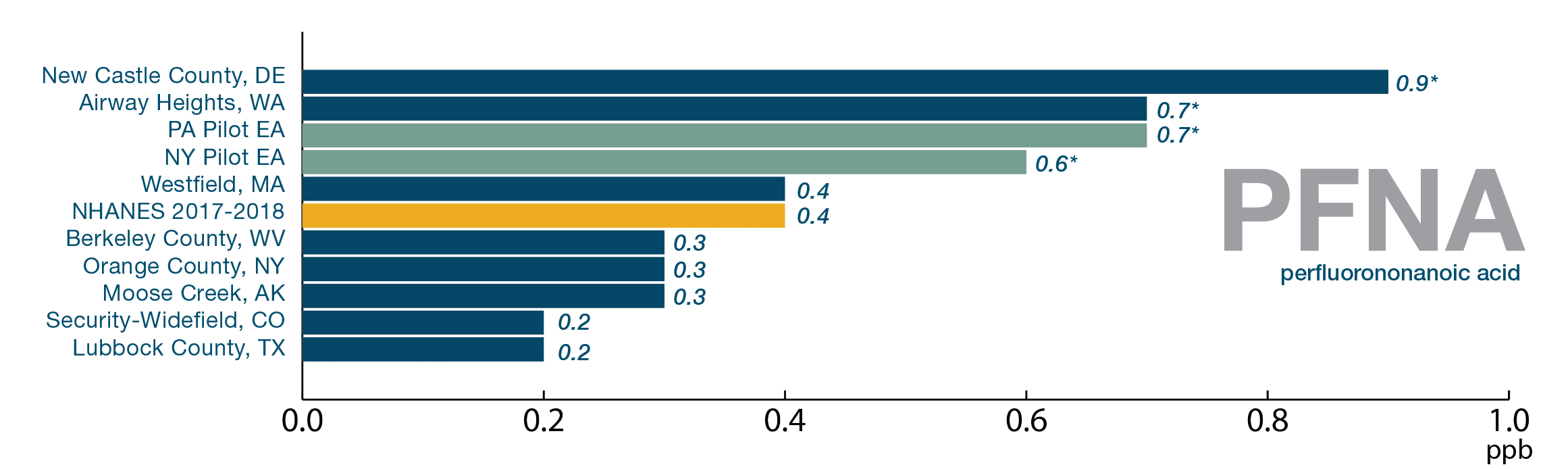

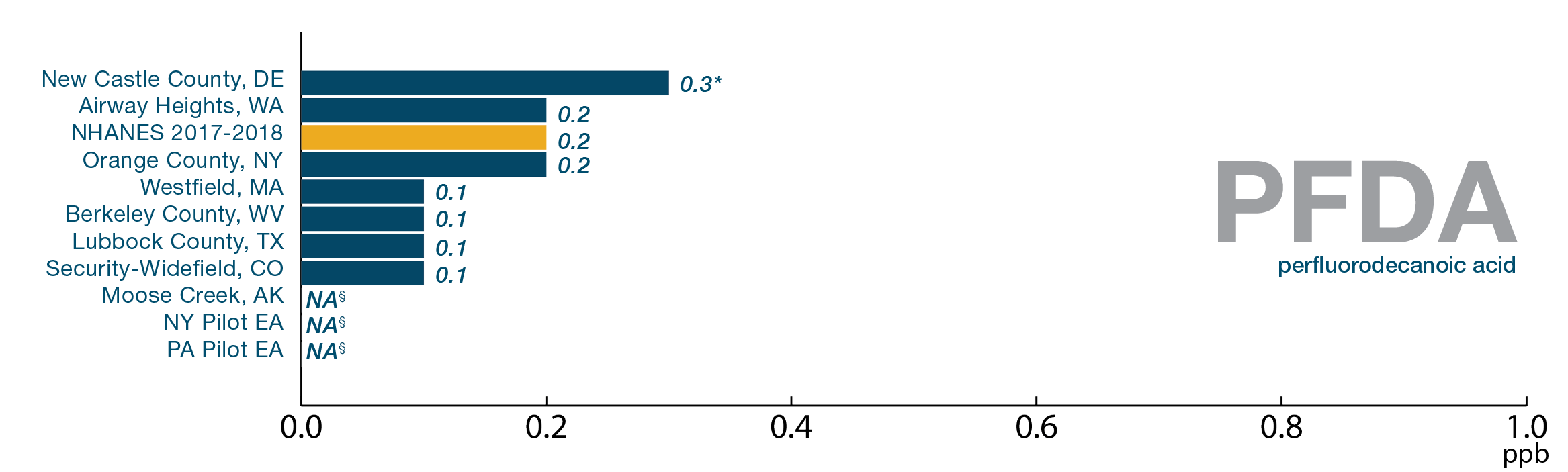

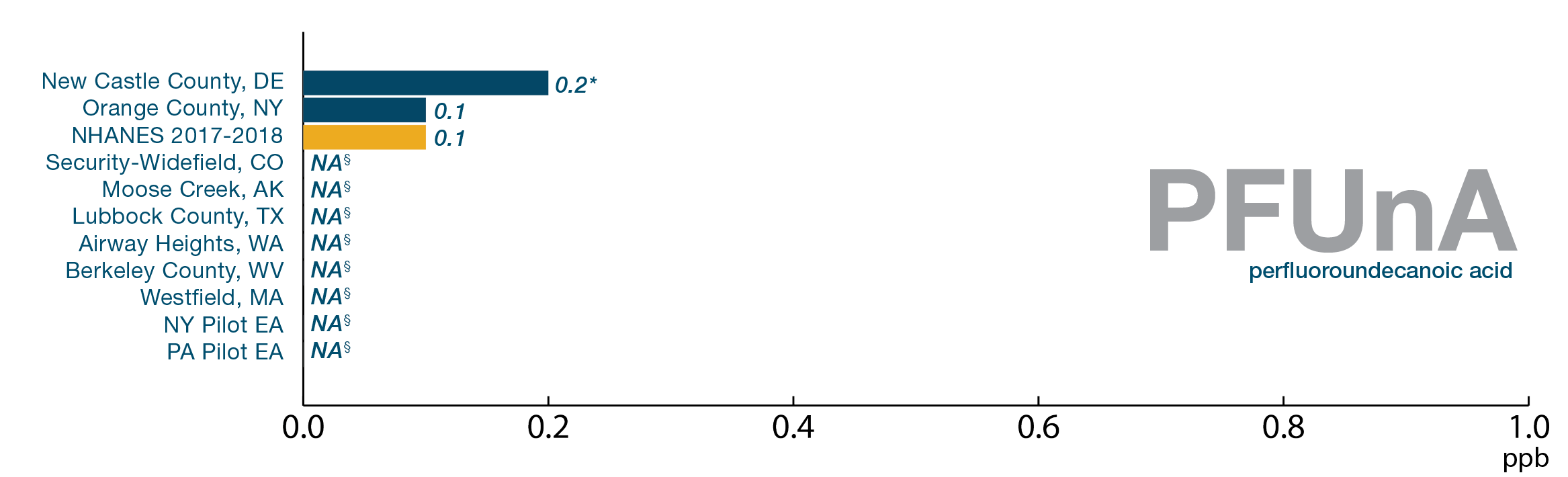

Average age-adjusted blood levels of PFAS

The levels of PFAS are higher than national levels in many, but not all EA communities:

PHFxS is higher in ten of ten EA communities.

PFOS is higher in eight of ten EA communities.

PFOA is higher in seven of ten EA communities.

PFNA is higher in four of ten EA communities.

PFDA and PFUnA are higher in one of ten EA communities.

MeFOSAA levels were not statistically elevated at any site.

Results also showed that:

Elevated blood levels of PFHxS, PFOS, and PFOA may result from past drinking water contamination.

Participants with higher levels of PFHxS, PFOS, and PFOA in their drinking water generally had higher PFHxS, PFOS, and PFOA blood levels.

PFHxS, PFOS, and PFOA were previously detected at elevated levels in drinking water at all EA sites.

It takes a long time for PFAS to leave the body. So, past drinking water exposure may have contributed to the PFAS blood levels found in EA participants years later.

Participants with elevated blood PFHxS levels typically had elevated PFOS and PFOA blood levels.

This suggests a common source of exposure like drinking water supply. It also suggests a common contamination source, such as AFFF. Other sources of exposure were not measured but could have contributed to PFAS in participants' blood.

Long-time residents had higher PFHxS, PFOS, and PFOA blood levels; they likely drank the contaminated water the longest.

The amount of drinking water a participant consumed was associated with PFHxS blood levels.

Adults using one or more filter or treatment devices in their homes and adults who reported not drinking tap water at all had lower PFHxS, PFOS, and PFOA blood levels than those who did not.

Average PFOS and PFOA blood levels decreased in adult participants after the drinking water exposure stopped or was reduced.

Charts

The Average PFAS blood levels (age-adjusted) at PFAS EA sites compared to national levels is shown in the bar charts below.

FAQs: Demographics

PFAS blood levels varied by demographic and exposure traits of participants.

Interpreting results

The strength of these results varied, and they should be interpreted with caution. Some of these associations may be due to chance as we were testing many associations at once.

Variables

ATSDR used statistical models to study relationships between various demographic characteristics and lifestyle variables of the tested residents (1,791 adults and 197 children) in the eight ATSDR-led EAs. In general, the models showed the following.

Age

Blood levels of PFHxS, PFOS, PFOA, and PFNA were higher in older adults, and the size of the effect was stronger in females.

In children (3 to 17 years old), PFHxS and PFOA levels decreased for every additional year in age.

Sex

Males had higher blood levels of PFHxS, PFOS, PFOA, and PFNA. The difference between males and females was larger in younger adults.

In children, blood levels in males were higher than females for PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, and PFDA.

Race/Ethnicity

Race and ethnicity were associated with PFNA blood levels in adults and children. Compared to those who identified as non-Hispanic White, some groups had higher PFNA blood levels, while others had lower PFNA levels.

Cleaning

Adults who reported cleaning their homes more frequently had higher PFNA blood levels than those who cleaned a few times per year or less.

Soil contact

Children who reported more frequent contact with soil had higher levels of PFOS, PFNA, and PFDA.

Locally grown produce and dairy

Adults and children who reported eating locally grown fruit and vegetables had higher PFDA blood levels.

Adults who reported drinking locally produced milk, even occasionally, had higher PFHxS and PFOA blood levels compared to those who did not.

Stain-resistant products

Participants who reported using stain-resistant products a few times per year or more had blood levels of PFNA that were higher than participants who never used them.

Childbirth

Women who had given birth had lower PFHxS blood levels than those who had not.

Breastfeeding/formula

Every additional month of reported breastfeeding was associated with an increase in PFDA blood levels in child participants.

Every additional month of formula consumption was associated with an increase in PFNA blood levels in child participants.

FAQs: Testing and results

What did other testing find?

PFHxS, PFHxA, and PFBA were detected in urine and at low concentrations.

Almost all tap water samples collected during the ATSDR-led EAs were below all federal and state guidelines for PFAS in drinking water at the time the samples were collected. Two of the 176 samples collected had PFOS measured above ATSDR's screening value for PFOS in drinking water.

PFAS contamination in house dust was similar to that reported in other studies (with and without known PFAS contamination).

What do these results mean for the EA community?

The PFAS EAs provide evidence that past exposures to PFAS in drinking water have impacted the levels of PFAS in people's bodies. PFAS are eliminated from the body over a long period of time. This allowed ATSDR to measure PFAS even though exposures through drinking water were mitigated, or lowered, years ago.

Although the exposure contribution from PFAS in drinking water has been mitigated (reduced), there are actions community members and stakeholders can take to further reduce exposures to PFAS and protect public health.

FAQs: What else can be done?

The community

For information on water quality, become familiar with Consumer Confidence Reports.

Private well owners living in the area affected by PFAS should consider having their wells tested for PFAS if testing has not been conducted before.

Verify a water filter's ability to reduce PFOA and PFOS. NSF International, the global health organization, developed a test method to verify a water filter's ability to reduce PFOA and PFOS to below the health advisory levels set by the EPA.

To find NSF International-approved devices, go to the bottom of the NSF Certified Drinking Water Treatment Units page. Then check the boxes for PFOA Reduction and PFOS Reduction.

Nursing mothers should continue breastfeeding. Based on current science, the known benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risks for infants exposed to PFAS in breast milk.

Eliminate or decrease potential exposure to PFAS when possible. This pertains to consumer products such as stain-resistant products and food packaging materials.

Pay attention to advisories about food consumption, such as local fish advisories.

Discuss any health concerns or symptoms with your health care provider. Share results of PFAS blood testing with your health care provider and make them aware of ATSDR resources for clinicians.

Follow the advice of your health care provider and the recommendations for checkups, vaccinations, prenatal care, and health screening tests.

For your child, follow the advice of their health care provider and the recommendations for well child checkups, vaccinations, and health screening tests. Consult My Health Finder to help identify those vaccinations and tests.

For more information about environmental exposures and children's health, contact the Pediatric Environmental Health Specialty Units, a nationwide network of experts in reproductive and children's environmental health.

Water providers

ATSDR does not recommend an alternate source of drinking water at this time. This is based on the PFAS drinking water test results from sites with public water supplies. However, operators of affected public water systems should continue to monitor concentrations of PFAS in drinking water delivered to EA communities. They should also properly maintain treatment systems to ensure that concentrations of PFAS remain below the existing federal and state guidelines for specific PFAS in drinking water. Results of PFAS monitoring should be shared with community members through appropriate communication channels.

The Air Force is encouraged to continue providing bottled water and/or water filtration systems for households with private wells with PFAS concentrations above relevant state or federal guidelines unless a different alternative source of drinking water that meets all guidelines has been provided. Testing should continue to be made available for private wells for PFAS if new data indicate they may be impacted by PFAS-containing groundwater. Households with private wells that receive bottled water and/or have water filtration systems installed specifically to treat water to remove PFAS should continue to use these alternative sources of water.

Actions

Federal and state regulatory agencies can consider the EA findings about PFAS blood levels and the amount of PFAS that was in drinking water for policy development.

ATSDR recommends monitoring PFAS in drinking water in more communities (beyond those that were studied in the EAs) to improve the ability to identify and respond to communities affected by PFAS.

ATSDR will continue to share information about ongoing research related to the potential health effects of PFAS exposure.

Fact sheets and report

- PFAS Exposure Assessments, Collective Findings Across Ten Exposure Assessment Sites, Final Report (9/22/2022)

- PFAS Exposure Assessments, Collective Findings Across Ten Exposure Assessment Sites, Appendix A, B, and C (9/22/2022)

- PFAS Exposure Assessments, Collective Findings Across Ten Exposure Assessment Sites: Community Summary (9/22/2022)

- CDC/ATSDR PFAS Exposure Assessment Protocol (6/11/2020)