Key points

- PFAS drinking water contamination was identified in the Security-Widefield exposure assessment (EA) site.

- ATSDR found that the public drinking water supply currently meets or is below EPA's 2016 health advisory.

- Community members getting water from Security Water District, Widefield Water and Sanitation District, or Security Mobile Home Park don't need to use alternative water sources.

Background

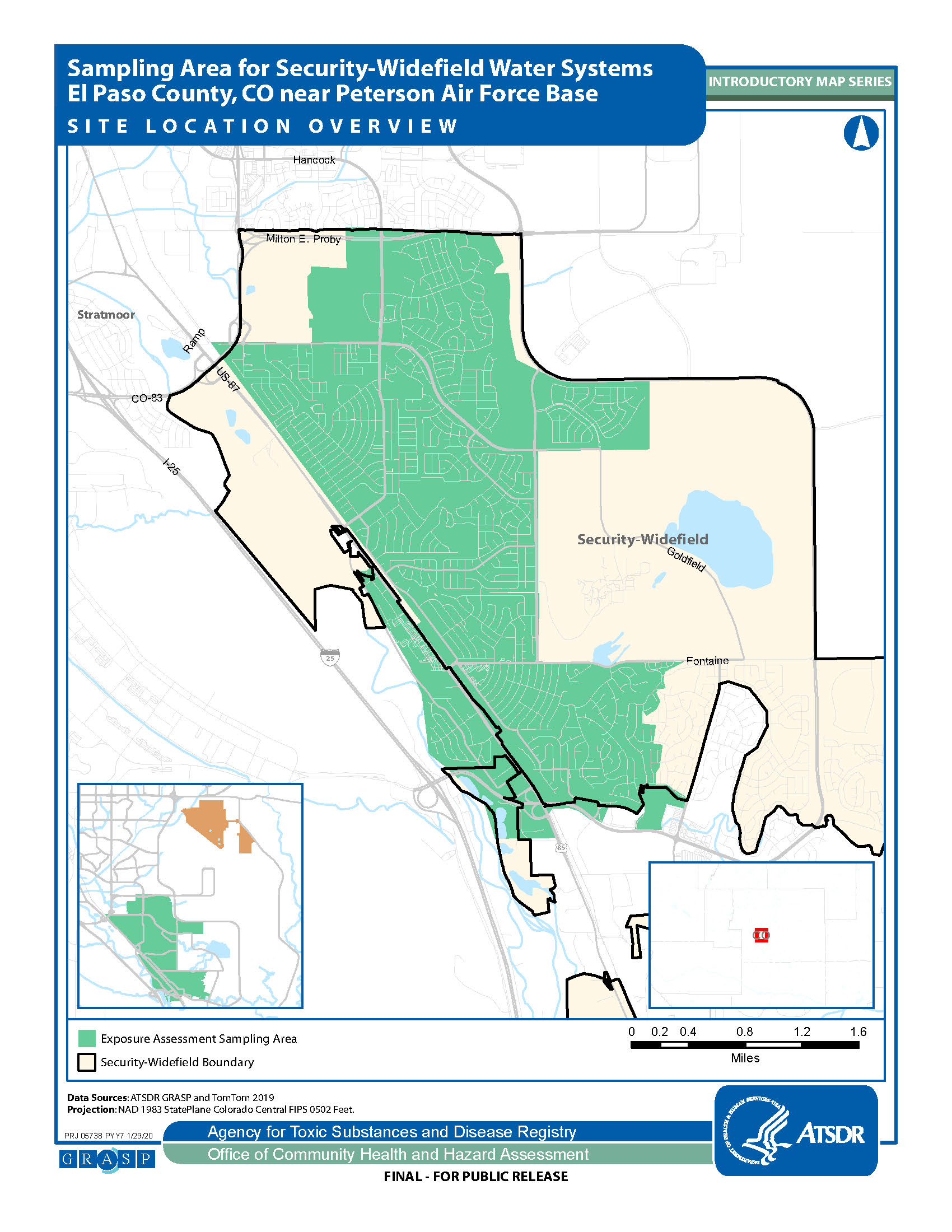

In 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) conducted an exposure assessment (EA) in Security-Widefield, El Paso County, Colorado, near Peterson Air Force Base (the Base).

Individual test results were sent to participants from CDC and ATSDR. They also released summary results to the community in May 2021. The per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) exposure assessment report was released in June 2022.

In 2019, CDC/ATSDR established a cooperative agreement with researchers at the Colorado School of Public Health (Colorado SPH) at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. The cooperative agreement was established to conduct a health study called the Colorado Study of Community Outcomes from PFAS Exposure (CO-SCOPE).

This study is part of the ATSDR PFAS Multi-site Study (MSS), a larger study that aims to expand knowledge about PFAS exposure and health outcomes among different populations.

Why the Security-Widefield EA site was selected

When selecting EA sites, ATSDR considered the extent of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) contamination in drinking water supplies. It also considered:

- The duration that exposure may have occurred.

- The number of potentially affected residents.

The Security-Widefield EA site was identified with PFAS drinking water contamination from products like aqueous film forming foam (AFFF). As early as the 1970s, the Base used AFFF containing PFAS for firefighter training. Over time, the PFAS entered the ground and moved into the groundwater to offsite locations and nearby municipal wells.

PFAS were first detected in municipal wells downgradient of the Base in 2013. These supplied water to the Security Water District (WD), the western portion of the Widefield Water and Sanitation District (WSD), and the Security Mobile Home Park (MHP). Between January and November of 2016, Security WD and Widefield WSD took contaminated groundwater wells offline and shifted to uncontaminated surface water sources.

In 2017, Widefield WSD installed an ion exchange system to treat PFAS in water from its contaminated wells. Security WSD currently uses uncontaminated surface water sources. Residents of Security MHP were provided bottled water beginning in the summer of 2016 until a treatment system was installed in November of 2017.

ATSDR has determined that the public drinking water supply in Security-Widefield currently meets or is below the EPA's 2016 health advisory (HA). At this time, ATSDR does not recommend alternative sources of water for community members getting drinking water from Security WD, Widefield WSD, or Security MHP.

Sampling area

Timeline

Information session

Meeting date: 08/04/20

Recruitment begins

Letters sent following the information session

Letters sent 08/03/20

Phone calls start 08/06/20Field work/sample collection

Began 09/15/20

Ended 09/28/20Samples analyzed

Completed

Individual test results

Mailed 05/07/21

EA site report

Findings and recommendations released 06/14/22

Community meeting

Met 06/28/22

How testing was conducted

ATSDR invited randomly selected households to participate in the PFAS EA. To be eligible to participate, household residents must have:

- Received their drinking water from Security WD, Security MHP, or the western portion of the Widefield WSD.

- Used this water for at least 1 year before November 10, 2016.

- Been older than three years at the time of sample collection.

- Not been anemic or had a bleeding disorder that would prevent giving a blood sample.

Households with private wells were not eligible to participate. Measuring PFAS in the blood from randomly selected households allows us to estimate exposure from consumption of public drinking water for the entire community in the affected area. This includes even those who were not tested.

What test results mean for the community

This EA shows that past exposures to PFAS in drinking water have impacted the levels of some PFAS in residents.

These PFAS are eliminated from the body over a long period of time. This allowed ATSDR to measure PFAS even though exposures through drinking water were mitigated, or lowered, years ago.

The exposure contribution from PFAS in drinking water in Security-Widefield has been reduced. There are still actions the community and city officials can take to reduce exposures to PFAS even more.

Based on the test results from drinking water wells in Security-Widefield, ATSDR does not recommend an alternate source of drinking water at this time.

Results

In May 2021, CDC/ATSDR released a summary of the biological and environmental test results. The full report was released May 24, 2022, and a summary of its findings are below.

In September 2020, ATSDR collected samples and other information from participants. ATSDR analyzed data from:

- 346 people, including

- 318 adults.

- 28 children.

- 318 adults.

- 188 households.

- Questionnaires completed by all participants.

- Blood and urine samples provided by most participants.

- Tap water and dust samples from some homes.

ATSDR sent individual results to each participant in May 2021.

Key takeaways

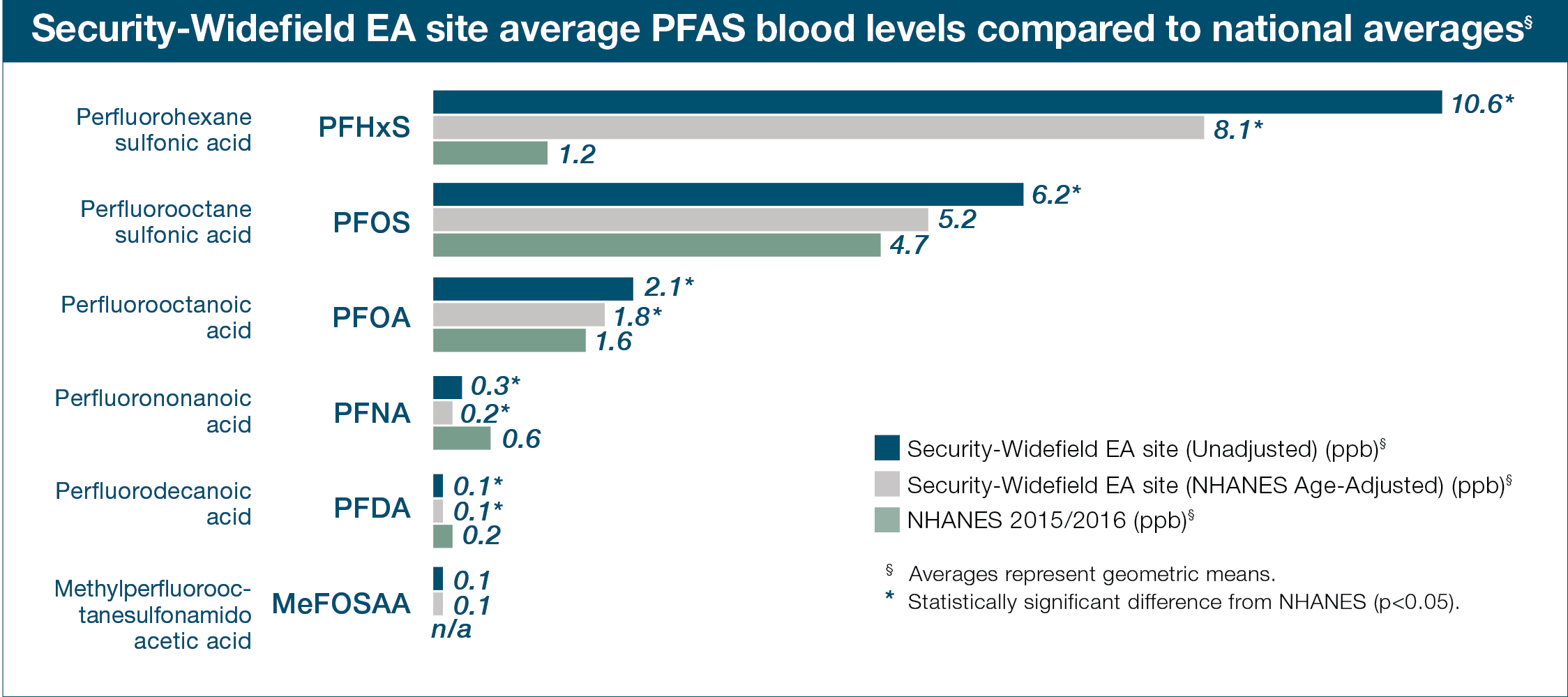

Levels of PFHxS and PFOA in the blood of the Security-Widefield EA participants were up to 6.8 and 1.2 times the national levels, respectively. In addition:

- Other PFAS were not higher than the national average or were detected too infrequently.

- Elevated blood levels may be linked with past drinking water contamination.

- Some demographic and lifestyle characteristics were linked with higher PFAS blood levels.

All tap water samples collected during the EA in 2020 met the EPA's 2016 HA for specific PFAS in drinking water.

Additional testing at the site

Only one PFAS—perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA)—was detected in urine. It was detected at low concentrations.

All tap water samples collected during the EA in 2020 met EPA's 2016 HA for PFAS in drinking water.

PFAS contamination in house dust was similar to that reported in other studies (with and without PFAS contamination). This likely contributed to PFAS levels in the blood.

Future direction

What was learned about PFAS levels in blood

Did you know?

Of the seven PFAS tested at the Security-Widefield EA site, six were detected in more than 67% of the blood samples collected:

- PFHxS

- PFOS

- PFOA

- PFNA

- PFDA

- MeFOSAA

Since 1999, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) has measured PFAS levels in blood in the U.S. population. PFAS levels are shown to be age dependent and tend to increase with age in part due to longer periods of exposure.

ATSDR adjusted blood levels of study participants at the Security-Widefield EA site for age to allow for meaningful comparison to the NHANES dataset. After adjustment, two PFAS were higher than national levels, but slightly less so. Age-adjusted averages are more representative of the Security-Widefield EA site community.

Information to protect our communities

Did you know?

PFHxS, PFOS, and PFOA were detected in Security-Widefield water systems as early as 2013. It is thought that contamination likely began earlier. Blood levels of PFHxS and PFOA were statistically elevated compared to national averages.

By November 2016, actions taken by the three affected water systems reduced PFAS levels in drinking water below EPA's 2016 HA. There were more than 3 years and 10 months between the reduction of exposure via contaminated drinking water and the collection of the EA blood samples.

Due to the long half-lives of PFHxS, PFOS, and PFOA in the human body, past drinking water exposures may have contributed to the EA participants' blood levels. Typically, participants who had elevated blood levels of one of the three PFAS also had elevated levels of the other two PFAS. This suggests a common source of exposure, such as the Security-Widefield public drinking water supplies. Other sources of exposure were not measured but could have contributed to PFAS concentrations measured in blood of the EA participants.

It was found that:

- Long-time residents had higher PFHxS and PFOA levels.

- Adults who did not drink tap water at home had lower PFHxS and PFOA blood levels.

Statistical findings

ATSDR used statistical models to study relationships between various demographic characteristics and lifestyle variables of the tested residents. The models showed that, in general:

PFHxS, PFOS*, and PFOA levels in blood were higher in older participants.

Blood levels for these compounds in males increased by 1% to 1.7% for every year of participant age.

Blood levels for these compounds in females increased by 1% to 2.5% for every year of participant age.

Males had higher blood levels of PFHxS and PFOS* than females.

Residents reporting occupational exposure to PFAS in the past 20 years had lower blood levels of PFHxS (28%).

Residents with a history of kidney disease had PFHxS blood levels that were 39% lower than those who did not.

Adults who cleaned their homes an average of 3+ times per week had 24% higher PFOS levels than residents who reported cleaning a few times per month or less*.

Residents consuming locally grown produce had 52% higher PFOS blood levels.*

*PFOS blood levels were not elevated in the community.

Exposure in children

Infants born to mothers exposed to PFAS can be exposed in utero and while breastfeeding. However, based on current science, the benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risks for infants exposed to PFAS in breast milk.

The longer a child was breastfed, the higher their blood levels of PFOS and PFOA were when compared to non-breastfed children.

Children who drank formula with tap water had lower blood levels of PFHxS, PFOS, and PFOA than children who never drank formula with tap water.

Because of the small sample size, results should be interpreted with caution. ATSDR will gather the data from children across all exposure assessment sites and provide a detailed analysis.

What the community can do

For information on water quality, become familiar with Consumer Confidence Reports.

Verify a water filter's ability to reduce PFOA and PFOS. NSF International, the global health organization, developed a test method to verify a water filter's ability to reduce PFOA and PFOS to below the HA levels set by the EPA.

To find NSF International-approved devices, go to the bottom of the Search for NSF Certified Drinking Water Treatment Units page then check the boxes for PFOA Reduction and PFOS Reduction.

Nursing mothers should continue breastfeeding. Based on current science, the known benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risks for infants exposed to PFAS in breast milk.

Eliminate or decrease potential exposure to PFAS when possible. This pertains to consumer products such as stain-resistant products and food packaging materials. Refer to Questions and Answers on PFAS in Food for more information.

Pay attention to advisories about food consumption, such as local fish advisories.

Discuss any health concerns or symptoms with your health care provider. Share results of PFAS blood testing with your health care provider and make them aware of ATSDR resources for clinicians.

Follow the advice of your health care provider and the recommendations for checkups, vaccinations, prenatal care, and health screening tests.

Join the multi-site health study funded by ATSDR. This includes the El Paso County area. The study is called the Colorado Study on Community Outcomes from PFAS Exposure (CO-SCOPE).

Follow the advice of your child's health care provider. This includes well-child checkups, vaccinations, and health screening tests. Visit MyHealthfinder for more information.

Find more information on environmental exposures and children's health.

What Security WD, Widefield WSD, and Security MHP can do

Operators of public water systems should continue to monitor concentrations of PFAS in drinking water delivered to the Security-Widefield community. This will ensure that concentrations of PFAS remain below the EPA's HA or other applicable guidelines for specific PFAS in drinking water.

Results of PFAS monitoring should be shared with community members through the appropriate communication channel.

All treatment systems to remove PFAS from the municipal drinking water in Security-Widefield should be properly maintained.

Resources

- PFAS Exposure Assessment, El Paso County, Colorado: Report (6/14/2022)

- PFAS Exposure Assessment, El Paso County, Colorado: Report Appendix (6/14/2022)

- PFAS Exposure Assessment, El Paso County, Colorado: Report Consumer Summary (6/14/2022)

- PFAS Exposure Assessment, El Paso County, Colorado: Fact Sheet

- PFAS Exposure Assessment, El Paso County, Colorado: Community-Level Summary Results Fact Sheet