Clinical Assessment – Tests

Upon completion of this section, you will be able to

- Describe chest radiograph findings associated with other asbestos-associated diseases and

- Describe pulmonary function test findings associated with asbestosis.

The most important tests in diagnosing asbestos-associated disease are

- Chest radiographs and

- Pulmonary function tests.

Other tests and procedures that are sometimes used to diagnose asbestos-associated diseases by specialists in cases that require further work-up include

- Blood studies,

- Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL),

- Colon cancer screening.

- Computed tomography (CT) or high-resolution, computerized (axial) tomography (HRCT), and

- Lung biopsy.

Screening pulmonary function tests are useful for finding restrictive deficits most commonly associated with asbestosis (see table). Findings may include a reduction in forced vital capacity (FVC) with a normal forced expiratory volume (FEV) in one second FEV1/FVC ratio. Some sources report abnormal pulmonary function tests in 50% to 60% of patients with asbestosis [Ross 2003].

In some cases, combined patterns of restrictive and obstructive disease may be seen. For further assessment of whether a patient has a restrictive abnormality and asbestosis, additional, more specialized tests may be required.

- Carbon monoxide diffusion capacity (DLco), which is very sensitive to ventilation-perfusion mismatch and gas exchange abnormalities characteristic of all types of diffuse interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, is reduced in 70% to 90% of asbestosis cases [Ross 2003]. Be aware however that low DLco is a non-specific finding and it can be present in far advanced stages of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as well as in other types of restrictive interstitial diseases.

- Static lung volumes measured by plethysmographic or helium dilution methods.

Consider consulting a pulmonologist if the diagnosis is unclear, if there is a rapid decline in pulmonary function, or if there is a potential need for a tissue biopsy or BAL, such as in cases where lung cancer, mesothelioma, or an infection is suspected. The pulmonologist may recommend more extensive pulmonary function tests.

| Asbestos-Associated Disease | Findings |

|---|---|

| Asbestosis |

Restrictive spirometry pattern (i.e., low FVC with normal FEV1/FVC ratio. Mixed obstructive/restrictive spirometry pattern (i.e., reduced FEV1/FVC ratio with reduced FEV1) [American Thoracic Society 2004]. Decreased DLco [American Thoracic Society 2004]. |

| Asbestos-related pleural abnormalities | Normal pattern or if extensive pleural involvment, restrictive spirometry pattern [Larson et al. 2012]. |

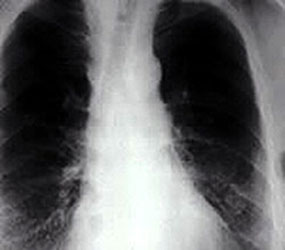

The chest radiograph is used primarily to find, localize, and assess the extent of structural changes associated with asbestos-caused chest diseases (asbestosis, non-malignant pleural disease, mesothelioma, and lung cancer).

Diagnosis of asbestosis should mostly but not totally be based on radiographic findings, per the diagnostic criterion of the American Thoracic Society. In 10% to 15% of cases, an asbestos-associated pulmonary function abnormality can occur without definite radiologic change [Ross 2003]. The association of pleural thickening and calcification with interstitial changes enhances diagnostic accuracy of asbestosis.

During the latter half of the past century, the International Labour Office (ILO) developed a system for radiographic classification of the pneumoconiosis. It now includes a set of standard digital radiographic images or a set of standard plain film images. [ILO 2011, NIOSH 2011b] Persons certified by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) as proficient in the use of this rating system are called “B Readers.” Most epidemiological studies of pneumoconiosis use B Readers to classify radiographs according to the ILO system.

A current list of B Readers can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/chestradiography/breader-list.html. Classification of asbestosis by chest radiography should be guided by the ILO system.

A list of typical chest radiograph findings for each of the asbestos-associated diseases is in the table below.

Pleural Plaques |

Pleural Mesothelioma |

Asbestosis |

| Asbestos-Associated Disease | Typical Chest Radiograph Findings |

|---|---|

| Asbestosis |

Small, irregular opacities in both lung fields, predominating at the lung bases. Diffuse, bilateral interstitial fibrosis. With advanced disease, combined interstitial and pleural involvement can blur the heart border (also known as the “shaggy heart sign”). Honeycombing and upper lobe involvement in near end-stage disease. |

| Asbestos-related Non-malignant Pleural Abnormalities |

Pleural Plaques Often multiple bilateral well-circumscribed areas of thickening found on the pleura, sometimes with calcification (10%-15%) [Khan et al. 2013]. Non-malignant Pleural Effusions Indistinguishable from other pleural effusions, but usually small and can be either unilateral or bilateral. Diffuse Pleural Thickening Smoothly thickened parietal pleura often associated with obscuration of the costophrenic angle [Khan et al. 2013]. Sometimes, prominent interlobar fissures). Rounded Atelectasis Appears as a rounded intrapulmonary mass abutting on thickened pleura, with bands of lung tissue radiating outwards. |

| Lung cancer | Radiological appearance same as that of lung cancers with other causes (e.g., solitary pulmonary mass with or without mediastinal lyphadenopathy). |

| Mesothelioma | May present as a

|

In some cases, computed tomography (CT) scans, including high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scans can facilitate diagnosis of asbestos-associated diseases such as lung fibrosis due to their greater sensitivity and specificity than conventional chest radiographs [Vierikko et al. 2010; Parris et al. 2009]. Because they are associated with higher doses of radiation than conventional chest radiographs and their cost-effectiveness and efficiency as screening tools have not been established, CT scans are not currently recommended in the United States for routine screening of asbestosis of the general population.

They can be useful in further investigating abnormalities found on chest radiographs and in detecting abnormalities not seen on chest films of patients with dyspnea or pulmonary function abnormalities such as decreased DLco [Vierikko et al. 2010].

CT and HRCT scans are more sensitive and specific than chest radiographs. HRCT scans can be used particularly when abnormalities on a conventional chest radiograph are equivocal or when a conventional chest radiograph is normal in the face of unexplained lung function abnormalities in a patient with significant asbestos exposure [American Thoracic Society 2004]. They are especially useful in detecting

- Early parenchymal abnormalities of asbestosis,

- Early pleural disease, such as plaques and rounded atelectasis,

- The difference between asbestos-associated pleural plaques and extra-pleural fat, and

- Mesothelioma [British Thoracic Society 2001].

However, HRCTs are recommended for use in screening special populations at high risk of lung cancer such as people with smoking histories of 15 to 30 pack years and those with some occupational exposures such as asbestos, arsenic, chromium, silica, nickel, cadmium, berryllium and diesel fumes [Bach et al. 2012; NIOSH 2012b].

The utility of other imaging techniques such as ultrasound, gallium scanning, magnetic imaging, ventilation-perfusion studies, and positron emission tomography has not been established in asbestos-related disease.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is sometimes used by specialists to identify other possible causes for lung pathology. It can be used to assess exposure to asbestos by measuring the amount and type of asbestos bodies and asbestos fibers in the lavage fluid [American Thoracic Society 2004]. Not only is this a somewhat invasive procedure requiring fiberoptic bronchoscopy, but the laboratory procedures are not routinely available; special laboratory facilities and expertise are required.

Lung biopsy is a definitive test used in the histopathological confirmation of asbestos-associated diseases. Lung biopsies are rarely used to diagnose asbestosis or pleural plaques, because diagnosis of these conditions is usually based on medical and exposure histories, findings from the physical examination, and other tests. Appropriate referral to a specialist is indicated if lung cancer or mesothelioma is suspected, since a lung biopsy will be indicated under these conditions.

Blood studies may occasionally be useful for ruling out other causes of restrictive lung disease.

Evidence increasingly shows that asbestos exposure increases an exposed patient’s risk for colon cancer [IARC 2012]. Therefore, it is important to perform colon cancer screening on asbestos exposed patients starting at age 50 according to current guidelines [Agency for Health Care Research and Quality 2008].

The joint guidelines from the American Cancer Society, the U.S. multi-society task force for colorectal cancer, and the American College of Radiology can be found at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18322143 [Levin et al. 2008].

It is important to know what other conditions bear radiographic similarities to changes associated with asbestos-related disease (see table).

| Asbestos-Associated Disease | Similar Radiographic Appearance |

|---|---|

| Asbestosis |

|

| Asbestos-related non-malignant pleural abnormalities | General differential diagnoses

Pleural plaques may be confused with

Non-malignant asbestos-related pleural effusions may be confused with

Diffuse pleural thickening may be confused with

Rounded atelectasis

|

| Lung cancer | Lung cancer not related to asbestos. |

| Mesothelioma | All other causes of unilateral pleural masses. |

To help attribute pulmonary fibrosis to asbestos exposure, check the diagnostic guidelines suggested by the American Thoracic Society:

- Characteristic appearance on radiographic chest imaging or, when lung tissue is available, tissue histopathology.

- Exposure history (with appropriate latency period); and/or asbestos bodies or uncoated fibers found in sputum, BAL, or lung tissue; and/or pleural plaques (as a marker of exposure) and

- Other causes unlikely.

- Other findings that aid in documenting disease attributable to asbestos exposure include

- Abnormal spirometry test results (restrictive and/or obstructive pattern),

- Low DLco, and

- Ausculatory signs such as characteristic rales [Holland and Smith 2003; American Thoracic Society 2004].

Bilateral calcified pleural plaques are usually attributable to asbestos exposure, but unilateral pleural plaques should motivate a search for other causes such as old tuberculosis, empyema, or hemothorax. CT scanning is useful to make a definite diagnosis of rounded atelectasis [Khan et al. 2013].

As stated previously, sets of diagnostic criteria like the Helsinki criteria can help in attributing an individual patient’s lung cancer to asbestos exposure.

Malignant mesotheliomas are, for all practical purposes, readily attributable to past asbestos exposure

- Asbestosis is commonly associated with restrictive patterns on spirometry.

- Signs of asbestosis on chest radiograph include interstitial fibrosis and the “shaggy heart sign.”

- On chest radiograph, pleural plaques appear as well-circumscribed areas of pleural thickening, sometimes with calcification.

- On chest radiograph, pleural effusions caused by asbestos have the same appearance as effusions from other causes, though they are typically small.

- On chest radiograph, diffuse pleural thickening appears as a smooth prominence along the chest wall and interlobar fissure thickening, often with obscuration of the costophrenic angle.

- On chest radiograph, findings associated with rounded atelectasis appear as a rounded intrapulmonary mass that abuts on thickened pleura and has radiating bands of lung tissue.

- Asbestos-associated lung cancer has the same appearance as lung cancer from other causes.

- Chest radiograph findings associated with mesothelioma include pleural effusions or a pleural mass.

- CT and HRCT scans can be useful to clarify questionable pleural or parenchymal findings, and in diagnosing mesothelioma.

- Other tests that can be useful include BAL, lung biopsy, and colon cancer screening.